The Ashes of the Baronet's Heart

Originally written by Meredith M. Brown and published in the May 2004 edition of Historical Footnotes, the quarterly newsletter of Historic Stonington.

Stonington’s Evergreen Cemetery is my next-door neighbor. I visit it often to see the tombstones of my parents, John Mason Brown and Catherine Meredith Brown, and their friends who are buried there – among them the poets Stephen Vincent Benet and Rosemary Benet, the naval combat artist Griffith Baily Coale, the writer Grace Zaring Stone and the aviation expert and World War I British combat pilot Francis Vivian Drake – as well as my father-in-law, the diplomat and writer John L. Barnard.

Anthony Havelock

So I keep track of the headstones, and the evolving history of Stonington they portray – Palmers, Denisons, Williamses, Pendletons, joined more recently by Previtys, Abbotts, Maderias. One stone has caught my eye for decades. It is a large stone against the wall near the southwest corner. It stands apart from the family plots, facing into them. It reads:

Here lie the ashes of the heart of

Anthony Havelock – Allan

Baronet

1904 - …

Close to the place where lie with those

Of her forebears the mortal remains

Of his most dear love for 23 years

“She was like a field of flowers in sunlight”

If the stone and its message were not already captivating, this past winter a tree fell westward along the south wall of the cemetery, clasping the baronet’s stone in its branches. Who was the baronet? Who was his most dear love? Is the baronet dead? If so, why is no date of death cut into the stone? If he is dead, are the ashes of his heart under the stone? If not, why not?

I showed the stone to my brother, Preston, this last fall. Its unabashed romanticism hooked him. He dug up information about the baronet on the Internet, sent it to me, and urged me to find out about “his most dear love.” Here’s what I’ve found so far.

The Baronet

Sir Anthony Havelock-Allan did die, in London on January 11, 2003, aged 98, after a long and distinguished career in the film business. He started as a casting director in 1933 (he helped to discover Vivien Leigh), became an associate producer for Noel Coward, and teamed up with the director David Lean to make such movies as In Which We Serve (1942), Blithe Spirit (1944), Brief Encounter (1945), Great Expectations (1946), and Oliver Twist (1948). He produced Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet in 1968 and rejoined Lean in 1970 to make his last movie, Ryan’s Daughter.

One obituary quoted Havelock-Allan on the reason Brief Encounter – an understated story of a married woman and a doctor who fall for each other – was emotionally powerful: “It was what left unsaid that was so erotic and moving. Today it seems obligatory that if you want to describe love to have to have two people humping around in a bed.”

Havelock-Allan came from a long line of distinguished soldiers. His paternal great-grandfather, Major General Sir Henry Havelock K.C.B., led the relief of Lucknow during the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857. Havelock-Allan succeeded to the baronetcy when his elder brother died in 1975.

In 1939 he married the actress Valerie Hobson, who played Estella in Great Expectations, among other roles. They were divorced in 1952. In 1979 he married Theresa Ruiz de Villafranca. One of the Internet articles displays a photograph of Anthony Havelock-Allan: slim, large-eyed, alert. The hair combed back from his high forehead is pomaded. He looks a bit like David Niven.

The baronet ordered the stone on April 27, 1978. In a letter to Buzzi Memorials in Pawcatuck dated March 10, 1978, he said they could leave the date of death blank, though he thought they “could safely put 19__”, because “to live to the year 2000, I should have to pass 96, which God forbid.” He did pass 96, by a couple of years. Though he died in January 2003, there still is no date of death on his stone, and no one has contacted Buzzi to commission one.

His Most Dear Love

I looked at neighboring plots to see who the baronet’s most dear love might have been. I saw no obvious Hollywood connections among the Palmers, Williamses, and Dixons nearby. I talked to several Stonington residents who knew of the story of the stone for the baronet’s heart. They identified the baronet’s dear love as Vivian Dixon Wanamaker. I found her grave in the Dixon plot, perhaps 100 feet from the baronet’s stone. Here’s the inscription on her gravestone:

Vivian Dixon Wanamaker

Born in New York, NU Jan. 11, 1918

Died in London Dec 1, 1974

Daughter of Arthur Dixon and Vivan Dixon

Nearby is the gravestone of the mother, Vivian Straus Dixon (1886-1967), a daughter of Isidor Straus and Ida Straus. The parents’ names were familiar to me. Isidor Straus, born in Rhenish Bavaria in 1845, emigrated to America when he was 9. The family prospered in the dry goods business in Georgia. After the Civil War, Straus moved to New York and, with his brother, acquired R.H. Macy & Co. He and his wife, Ida, died together on the Titanic in April 1912, his wife having declined his efforts to get her in a lifeboat with the women and children. She reportedly said: “We have been living together for many years, and where you go, I go.”

The Stonington residents to whom I talked had indirect memories of Vivian Wanamaker. Connie Dixon, widow of Francis (Frank) Dixon, for example, reported that Vivian was Frank’s cousin and that Frank had described her as “absolutely gorgeous.” Connie Dixon also reported that after Vivian’s death, the baronet from time to time would visit her grave or arrange to have flowers sent from Smith’s Florists in Westerly.

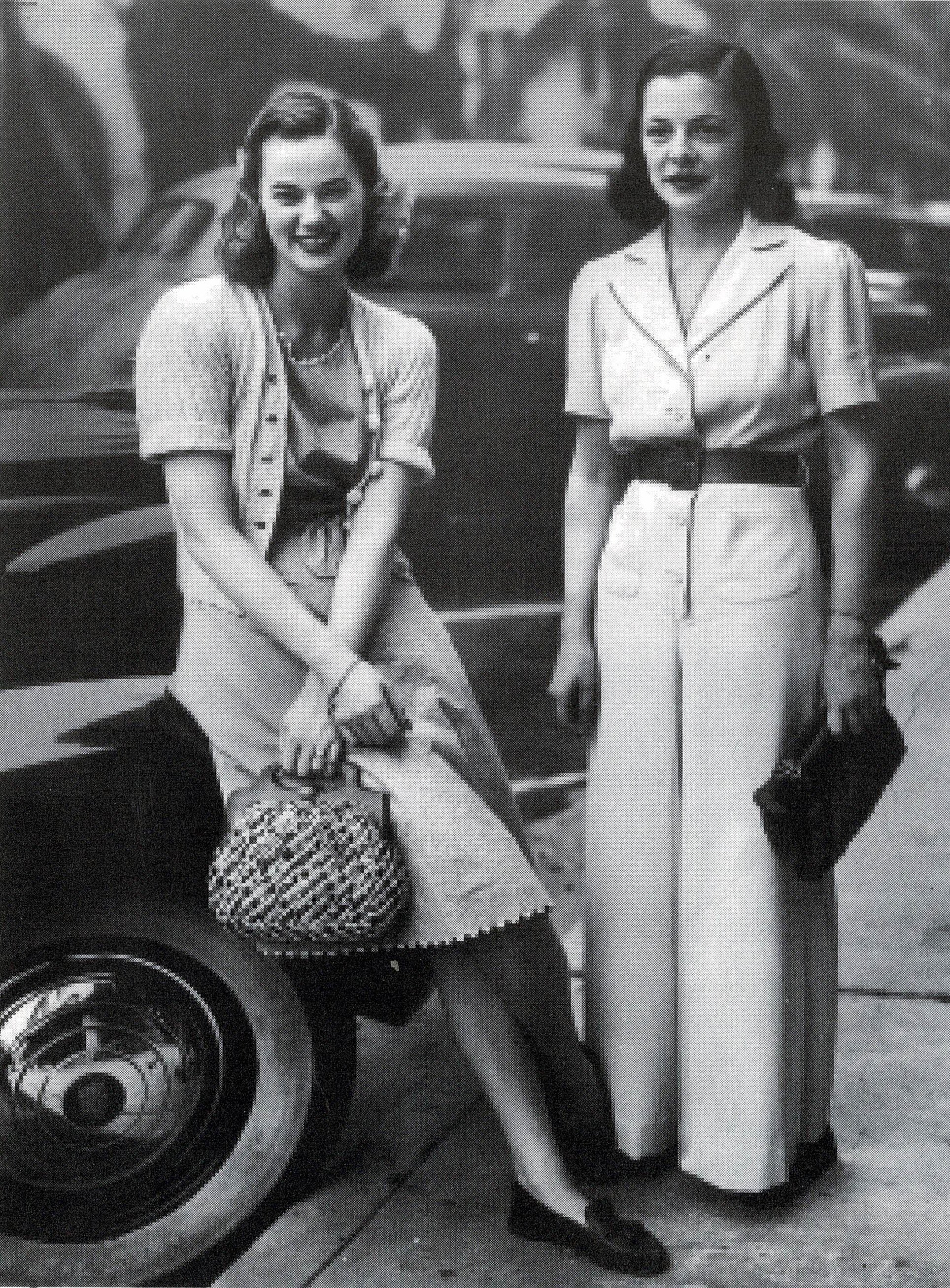

The Internet – and generous research help and suggestions from Mary Thacher, archivist and town historian – yielded more about Vivian Dixon Wanamaker. She was married twice. The New York Times on May 9, 1937, reported her marriage the previous day in Locust Valley, Long Island, to T. Dennie Boardman of Boston. According to the Times, Vivian “was introduced to society” the previous year, “attended Mlle. Chapon’s School in Paris, studied also in Munich and Florence,” and was the niece of Percy S. Straus, president of Macy’s.

The Times went on: “The couple had planned to be married on May 22, but the date was advanced suddenly so that they could take a wedding trip of a fortnight, which, owing to business engagements of the bridegroom, would not have been possible at a later date.” The story does not specify T. Dennie Boardman’s business. He is described instead as an “amateur golfer of note” and a graduate of St. Mark’s School and Harvard, and as a member of the Myopia Hunt Club, and of the Tennis and Racquet Club of Boston. (Lest you leap to the conclusion that the wedding had to be accelerated for reasons other than Mr. Boardman’s unidentified business engagements, you should know that their first child, Vivian, was not born until April 27, 1939.)

Vivian looks at us from her wedding story in the pages of the archives of the Times. She is, as Frank Dixon said, absolutely gorgeous. She looks like Vivien Leigh. One of the obituaries of Anthony Havelock-Allan notes that one of the first films he produced in the 1930s starred the young Vivien Leigh. “She had a beautiful face,” the baronet recalled, “but I didn’t think she was a natural actress.”

It is also fair to say that Vivian Dixon in her wedding picture resembled Valerie Hobson, the English actress who was Havelock-Allan’s first wife. Hobson retired from films in 1954 and married a member of Parliament. This second marriage was not always tranquil. Her husband was the notorious John Profumo, appointed by Harold Macmillan as Secretary of State for War in 1960. Soon after, Profumo, then in his late 40s, began an affair with a 21-year-old model and call girl named Christine Keeler, who was also having an affair with the Soviet naval attaché, Eugene Ivanov. After untruthfully denying his affair with Christine Keeler, Profumo was forced to resign and went into charity work. Hobson stuck by him until her death in 1998.

Vivian’s marriage to Dennie Boardman produced a daughter and a son but ended in divorce. Vivian then married Rodman Wanamaker, grandson of the John Wanamaker who founded the Wanamaker department stores (a Macy’s heiress marrying a Wanamaker’s heir). That marriage, in turn, ended in divorce in Reno, in November 1954.

On the baronet’s stone, he refers to “his most dear love for 23 years.” Backing up twenty-three years from the date of Vivian’s death in December 1974 would bring us to December 1951. Is it possible that the relationship between Havelock-Allan and Vivian Wanamaker contributed to Havelock-Allan’s divorce from Valerie Hobson in 1952? And also to Vivian’s 1954 divorce from Wanamaker?

It may also have been that Wanamaker, who was eighteen years older than Vivian, was not an easy man to be married to. His New York Times obituary in February 1976 reports that he had flown in World War I and, as a deputy police commissioner in New York City, had persuaded Mayor LaGuardia to add helicopters to the New York City police. He had played on the U.S. polo team in the 1924 Olympics. But it also notes that he was married four times. Vivian was his third wife. The previous marriages, to Alexandra Van Rensselaer Devereux and Beatrice Willing Patterson – nice names – also ended in divorce.

By 1954, Vivian and the baronet were both divorced. Connie Dixon remembers hearing that Vivian and the baronet lived together in England for some years. Why did they not marry? Vivian Dixon Wanamaker’s Times obituary in December 1974 reports her prominent role in New York and Palm Beach society, and says she lived in Rome and died in Westminster Hospital in London. “Burial will be on the family plot in Stonington, Conn. The service will be private.”

The Baronet’s Heart

Sir Anthony Havelock-Allan died on January 11, 2003 – a year and a half ago. Yet the date of death is not marked on the stone in the Stonington cemetery, and cemetery personnel say the plot has not been opened for burial of an urn or anything else. The baronet’s heart isn’t buried in Stonington. Will it ever be?

I have to doubt it. While the baronet was undoubtedly devoted to Vivian Dixon Boardman Wanamaker – witness the stone and its inscription, ordered by the baronet more than three years after Vivian’s death; witness the post-death visits and flowers – time passes. The late Clifford Mallory told Frank Dixon that a friend of Mallory’s – an Anglican clergyman who ultimately became bishop of Dover – had seen Havelock-Allan in Bermuda after Vivian’s death, recuperating from his loss in the company of other women. Based on what he had seen, the Anglican clergyman told Mallory that Stonington was never going to get so much as a toenail of the baronet.

In 1979, one year after the baronet ordered the stone, he married Maria Theresa Consuela de Villafranca (Sara), about whom I know only that she was the daughter of Carlos Ruiz de Villafranca. I suspect Sara came from the Ruiz de Villafranca family that was recognized by the king of Spain in the 1730s as part of the nobility of Orihuela, entitled to its own escutcheon. There still is a Ruiz de Villafranca palace in Orihuela, a town south of Valencia on the Mediterranean. Sara was listed as a survivor when the baronet died in 2003. It may well be that Sara has decided to be buried next to all of the baronet – including what’s left of his heart.

Many thanks to Chelsea Mitchell, Director of the Woolworth Library & Research Center Collections & Interpretation at Historic Stonington for sharing this story with us.